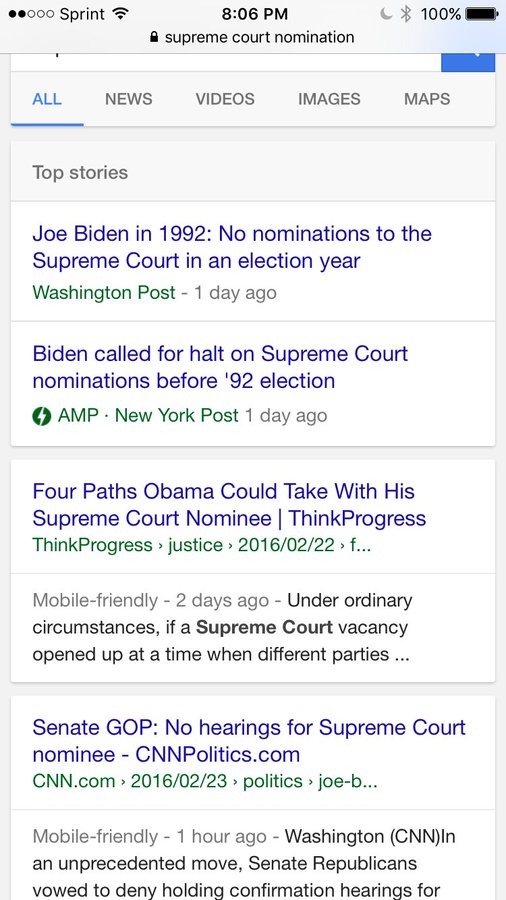

My favorite #AMP quote: “Saw an AMP icon in search results. The content loads like-yesterday-fast.” Thanks @rwaldron https://twitter.com/rwaldron/status/702298929937915904 …

Saw an AMP icon in search results… The content loads like-yesterday-fast

by WAN-IFRA Staff executivenews@wan-ifra.org | May 30, 2016

Richard Gingras wants the old internet back. Now the head of news and social products at Google, the entrepreneur has been riding the wave of digital media since 1979, when ‘digital media’ was broadcast Teletext. He helped launch Salon in 1995, the first web-only publication, and was its CEO until 2011. Speaking to Fairfax Media’s Julie Posetti at WAN-IFRA’s Digital Media Europe Conference in Vienna recently, he got nostalgic:

“You might remember 20 years ago when we all started playing around on the web, the term was we ‘surfed’ the web. You know, now it’s walking through six-inch mud. It’s not a surf, it’s a slog. And frankly I think we can do better.”

Gingras was talking about a new project curated by Google called AMP, or accelerated mobile pages. It is designed with one clear purpose: to speed up and clean up the web for mobile users. But his throwback to the ‘old days’ of surfing the web was also a warning about how the open internet ecosystem is succumbing to the creeping influence of proprietary platforms like Facebook, “walled gardens” of the internet, which he argues threaten professional journalism and free expression.

“This ecosystem of the web has been so valuable to society in so many ways that we have to be very careful of thinking that somehow it will just continue to be that way,” he says.

Google’s Global Partnerships President Daniel Alegre will be speaking on innovation at WAN-IFRA’s 23rd World Editors Forum in Cartagena, Colombia on 12 Jun 2016 to 14 Jun 2016. Google is also hosting a breakfast session on Tuesday to promote collaboration between the tech and journalism industry.

Google’s Global Partnerships President Daniel Alegre will be speaking on innovation at WAN-IFRA’s 23rd World Editors Forum in Cartagena, Colombia on 12 Jun 2016 to 14 Jun 2016. Google is also hosting a breakfast session on Tuesday to promote collaboration between the tech and journalism industry.

You can listen to his full interview in this episode of the Journalism Explainer podcast, where he discusses the open web, surviving the rise of ad blocking, the AMP project, and the future of media for journalists, advertisers and engineers alike.

The point of AMP, and early results

The AMP project (which is an open source collaborative effort involving thousands of publishers, including Fairfax Media, alongside Google) is an attempt to make surfing the web on mobile fast, simple and enjoyable. It sits somewhere between Facebook’s Instant Articles and an app for mobile— it’s a way for a publisher to create clean content for mobile, but it also allows customisation which Facebook doesn’t: ads, links back to your site, carousels which encourage you onto the next story. And Gingras stresses its open source nature, and Google’s attempts to partner with publishing platforms like WordPress. This isn’t just a tool for the big players.

“At this point, thousands of publishers are involved and it’s the most active open source project we’ve ever managed. There are 7,000 developers involved; obviously tens of thousands of publishers involved,” he says. “We’ve created working groups for each of the four segments of AMP functionality: the format itself, analytics, paywalls, ads – which by the way is open to anyone’s participation.”

My favorite #AMP quote: “Saw an AMP icon in search results. The content loads like-yesterday-fast.” Thanks @rwaldron https://twitter.com/rwaldron/status/702298929937915904 …

Rick Waldron@rwaldronSaw an AMP icon in search results… The content loads like-yesterday-fast

But Gingras says while the critical purposes of the AMP project are to improve the performance of the web and improve the ad ecosystem, he also says there is an important underlying purpose.

“There was a very, very significant secondary effect here that all of us were concerned about, particularly all of us who not only love the web for the ecosystem it is, but also recognise as publishers, recognise as Google, how valuable that ecosystem is: how do we make sure the web remains that healthy and compelling platform— I should say…it’s not quite a compelling platform at the moment— relative to proprietary platforms. That was very much a key objective here.”

The early data is encouraging.

“We’ve seen 100 to 150 percent increase in clickthroughs on ads, that’s a great number. And our best sense of that at this stage is because it’s a cleaner experience,” says Gingras. “The way it’s operating, the way people are using it, it is more respectful, so people are actually on the ads, and we’re seeing a 10 to 30 percent increase in effective CPMs.”

Ad blocking is a crisis, but also just a symptom

But those encouraging numbers stand alongside some more threatening ones. Gingras mentions the rate of ad blocking in Germany is now sitting somewhere between 35 and 40 percent; in France, it’s at 30 percent.

“Worse, if you look at it demographically, if you look at that key advertising segment of say 20 to 35 [year olds] it’s something like 55 per cent. Those are terrifying numbers. If we don’t think we have a crisis on our hands then we’re not looking at the numbers in a correct way.”

“Obviously, a lot of people can say ad blockers are terrible, and in a sense they are,” says Gingras. “But we can choose to take different approaches; probably should take both. One is [to fight] ad blockers— but beware how you approach that, because one of the reasons it’s at 35 to 40 percent in Germany is because there were very, very visible efforts to fight ad blockers legally, which simply served to promote to Germany the existence and availability of ad blockers. So that was kind of a dangerous play.”

“To me, the real issue with ad blockers is to recognise it as a symptom of an advertising system that is not currently what it needs to be, and that deserves addressing. That was one of the two things that the AMP project was very specifically focused on,” says Gingras.

“We have to address some underlying issues, and at core is respecting the consumer in the first place.”

The threat of walled gardens

But why is Google suddenly so interested in publishers?

Well, says Gingras, Google has matured. But it has also recognised a common interest between Google and publishers.

“Where publishers and Google have common cause is in the health of the web. We both depend upon it. [For] Google, if there were not a rich ecosystem of knowledge on the web, how is Google search a relevant product? We have significant ad platforms, which probably every publisher in this room uses to some extent, that [are] based on the health of the open web. Having that open environment of the web is absolutely crucial to building audiences, to creating new products and finding audiences for those products.”

“If over time the internet evolved to be primarily about proprietary platforms, that effort would be hugely more difficult and hugely more expensive. And I don’t say this as any criticism of Facebook,” says Gingras. “I understand what they’re trying to do, they’re smart people— but it is a proprietary, in a sense ‘walled garden’, platform.”

He gives Facebook’s new Instant Articles as an example of the risks the walled garden poses: “[Audiences] don’t come through the front door, they come through the bathroom window, and so you really need to take full advantage of that. The fact that I can’t do onward journeys in Instant Articles basically says I can’t build an engaged relationship with the user, much less get them to subscribe if I need subscription revenue.”

“The interesting thing is we may have common objectives, but we come at it from very different perspectives. We build services, we’re an engineering company, we’re not a media company. I have lots of folks who are great with code and sorry-arsed with words. And [with] publishers it’s kind of the reverse— I love talking to journalists far more than I love talking to engineers, but they write brilliant code. I could get in trouble for that,” he laughs.

It’s not the end for media— it’s the beginning

While many media commentators spell doom for publishers, Gingras has always been an optimist; he calls the digital age a “renaissance” for journalism. And while that might seem like a lofty call from a Google exec, his history with PBS, with Salon Media Group, as a current member on the board of the International Center for Journalists (this list really goes on), prove he is truly interested in journalism and free expression.

“[What you see] if you study media history is that a media product is born of its ecosystem, born of its marketplace, born of its distribution environment,” he says.

“If you look at the history of the modern American newspaper, the modern American newspaper was actually the result of the disruptive effects of television in 1947 to 1950, because it took and had a huge impact on the newspaper market. Dozens, hundreds of newspapers, thousands of newspapers shut down. You had two dozen newspapers in New York, you had eight newspapers in San Francisco. They went down to one and then they were left in a very powerful position, and then used that appropriately to build the modern American newspaper, which was a great product and a very profitable one.”

“But if you look at this environment here— I learned this when I was running Salon— that gardening site in The Dallas Morning News that generated a lot of revenue in its time and place, on the web is competing with 25 gardening websites that are focused just on that, with a value proposition for advertisers that’s much more direct. So it’s simply recognising that in this market you have to develop products that are appropriate to this competitive environment, where are the opportunities in the information economy that are appropriate to the audiences and the behaviours they expect in products.”

“We’re still at the early stages of the creative evolution of media products. I hope we’re talking in five years much more about new media forms.”

Julie Posetti is Fairfax Media’s Digital Editorial Capability lead and co-host of The Journalism Explainer podcast. Jake Evans is Digital Content Producer for Fairfax Media’s Learning Hub, where this post originally appeared.

WAN-IFRA Staff