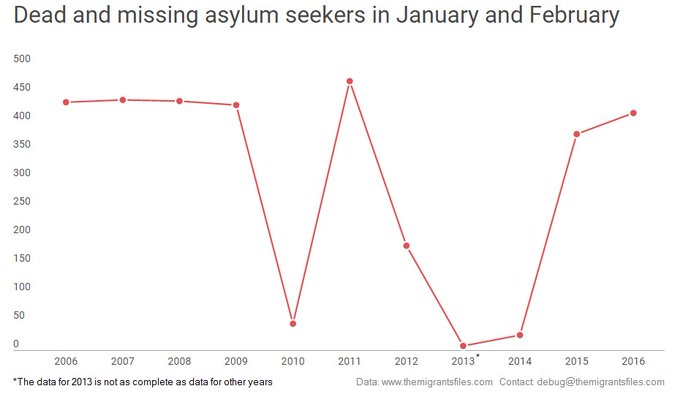

With over 400 #people dead on the borders of Europe, this year is still better than 2011http://bit.ly/24QlvEP

“If you want to reach Europe, for example from Libya to Italy, a person used to have a one in 10,000 chance of dying. With the Greek wall in place, that risk is now more like one in a 100,” said French data-driven journalist Nicolas Kayser-Bril. “It is now much much much more dangerous to cross into Europe,” he told the World Editors Forum.

Kayser-Bril, co-founder and CEO of the international data-driven storytelling agency Journalism ++, set up a unique cross collaboration between data journalists from newsrooms in different countries in Europe. Its aim was to establish a database that counts both the financial costs for refugees and migrants – and the Europeans receiving them – and the death toll of those who undertake the migration journey.

A group of journalists from over 15 European countries now collaborate on the migrants files. Their stories have appeared in Italy’s L’Espresso, Greece’s RadioBubble, Switzerland’s Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Sweden’s Sydsvenskan, France’s Le Monde Diplomatique, and Spain’s El Confidencial.

Data journalism identifies and measures trends

The project’s records show that more than 23,000 people have died since 2000. These numbers had quite some traction and allowed journalists to identify and measure trends.

The latest March 2016 update on the project shows that migrant routes have changed and that the number of deaths on the Eastern Mediterranean route has increased significantly.

While data journalism provides the bigger picture, Kayser-Brill points out that they take great care not to oversimplify the issue: “When someone dies on the way from Libya to Italy, it is clear he intended to reach Europe, but from Nigeria to Libya we don’t know if the final destination was Europe. So we flag in the database that maybe that person didn’t want to reach Europe.”

Holding power to account: a lack of migration numbers

Surprisingly, the numbers that were so crucial to the migration debate weren’t available. When the team approached national administrations to request the number of migration-related deaths, they came to realise that no such information was available, despite a 2013 European legislation compelling authorities to record and measure deaths.

“Interestingly, this lack of measuring wasn’t picked up by the media at all,” Kayser-Bril adds, “no administration was interested in measuring the issue”. In France for example, the authorities quite frankly told him: as soon as a person dies, he is no longer a migrant, so it is not a concern for the administration.

As a result of this project, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the UNHCR set up their own databases and now collect this data as part of their normal operation.

Migration coverage requires: numbers & emotions

In most countries around the world, the migration story has been dominated by two themes – numbers and emotions, according to the Ethical Journalism Network (EJN), which recently released ‘Moving Stories’, a report reviewing the media coverage on migration.

“In some cases, numbers and figures were twisted or exaggerated to portray asylum seekers as “sneaking in”, yet in other examples lengthy articles provided profiles of asylum seekers, or of those helping refugee organisations working in Calais,” the report reads.

Kayser-Bril says you need to measure an issue, not only to understand it but to also have a personal connection to it. “When we collect data, we collect personal stories and structure them in a way to make them comparable and measurable. It doesn’t mean that we ignore the human suffering behind every single number.”

“Projects like the Migrants’ Files play an essential role in covering the migration story, providing both accurate information and context for other journalists to draw upon so that media do not miss future opportunities to hold the EU and its members to account,” Tom Law, Communications Officer at the EJN told the World Editors Forum.

A milestone for cross-border journalism in Europe

The Migrants’ Files is a unique case of cross-border journalism on a low budget. With only € 7,000,- starting money, the project was done in a very lightweight format; putting the database at the centre, with no physical meetings and having documents translated in the journalists’ home countries.

As the team of reporters is employed in co-operating newsrooms, they have been able to generate stories using the findings from the project. This innovative cross-collaboration won a European Press Prize of € 10,000,- for last year, which is currently used to keep the newsletter and database running.