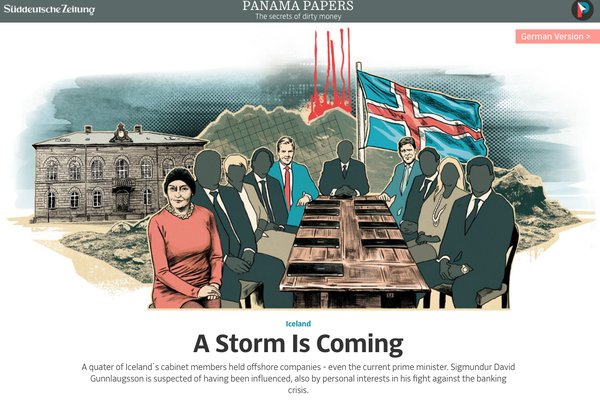

Biggest leak in the history of data journalism just went live, and it’s about corruption. http://panamapapers.sueddeutsche.de/en/

The largest-ever collaboration of its kind saw 400 journalists in 100 countries around the world working together to fulfill one of the core tasks of independent journalism: investigation.

“An internationally coordinated action forces states to react,” said Wolfgang Krach, Editor-in-Chief of Germany’s Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), at the annual World News Media Congress in Cartagena, Colombia, last week. “Nobody would have known about it. This business has been going on for decades. There were so many meetings from politicians saying they had to change it, but nothing happened,” Krach said.

He explained that “John Doe,” the anonymous source, leaked the 11.5 million encrypted internal documents from Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm that sells anonymous offshore companies around the world, out of a desire to expose the secret maneuverings of the world’s rich and famous.

“In Germany, we have a big discussion about the so-called ‘Lügenpresse’ [‘lying press’]. Can we still trust media organisations? And can we trust journalists? When we published the Panama Papers, it was very interesting to see how we regained trust from many readers, who congratulated us and said how important it is to have independent media organisations, journalists and newspapers,” Krach said.

The investigation was kept secret for a year

When the newsrooms were offered the undisclosed documents in spring of last year, they quickly realised they couldn’t do the investigation by themselves. They had to work together, not only because of the volume of the leak, but also because “you need to be familiar with the country, the politics, the language, the economic and social situation to research the documents,” Krach said.

Collaborating with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), with whom SZ has ongoing cooperation on several other leaks (including Offshore Leaks, Lux Leaks, and Swiss Leaks), they started looking for one journalistic cooperation partner in each affected country. But for the investigation to succeed, it had to remain secret – even in SZ’s own newsroom. “We invited about 100 international journalists to our conference room, and my colleagues asked me: ‘What the hell were all these journalists doing here?'” said Krach.

If keeping a secret in their own newsroom was difficult, finding external media organisations they could trust was an even bigger challenge. That was especially true in countries where press freedom is limited – where the police could raid newsrooms and confiscate documents. “That would mean all the research would have been over,” said Krach.

In fact, SZ still holds several documents pertaining to countries in which they haven’t found suitable partners.

“The biggest miracle is that nothing came out until 12 minutes before the worldwide embargo,” said Krach. That was when Edward Snowden tweeted the publication of the Panama Papers. Even today, nobody knows how he got that information.

How to handle 2.6 terabytes of data?

The most difficult aspect of such an enormous volume of documents – including e-mails, passports, letters, and so on – was to make them searchable, said Krach. The newsroom had to invest in computers and software to be able to systematically examine the files and analyse the information about tens of thousands of people from companies in more than 80 countries around the world.

While initially only seven out of the 600 journalists at SZ were involved, in late December that team was expanded to 25 people, including designers, illustrators and videographers. By March 2016, only a few weeks before publication, 15 more people came on board, including lawyers, translators, social marketing experts and a marketing team, which was in charge of branding the project.

SZ put up a paywall last year, and decided that the Panama Papers would not all be available free of charge.

Immediately after publication on Sunday, 3 April, at 20:00, the SZ site collapsed for several minutes. Traffic exploded, and by early afternoon Monday, 1.4 million people from abroad had visited the English-language site. Far more readers came from other countries than from Germany. Most of them were from Latin America.

While in the first few days some 40 stories were published, including videos, interactive graphics and a social media campaign, that number has decreased to three or four stories a week.